- Tips to Self-Edit Your Dissertation

- Guide to Essay Editing: Methods, Tips, & Examples

- Journal Article Proofreading: Process, Cost, & Checklist

- The A–Z of Dissertation Editing: Standard Rates & Involved Steps

- Research Paper Editing | Guide to a Perfect Research Paper

- Dissertation Proofreading | Definition & Standard Rates

- Thesis Proofreading | Definition, Importance & Standard Pricing

- Research Paper Proofreading | Definition, Significance & Standard Rates

- Essay Proofreading | Options, Cost & Checklist

- Top 10 Paper Editing Services of 2024 (Costs & Features)

- Top 10 Essay Checkers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- Top 10 AI Proofreaders to Perfect Your Writing in 2024

- Top 10 English Correctors to Perfect Your Text in 2024

- 10 Advanced AI Text Editors to Transform Writing in 2024

- Personal Statement Editing Services: Craft a Winning Essay

- Top 10 Academic Proofreading Services & How They Help

- College Essay Review: A Step-by-Step Guide (With Examples)

- 10 Best Proofreading Services Online for All in 2024

- Top 10 College Essay Review Services: Pricing and Benefits

- How to Edit a College Admission Essay (8-Step Guide)

- Improve Academic Writing: Types, Tips, Examples, Services

- How to Use AI to Write Research Papers: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write an Assignment: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students

- AI Proofreading Services: Meaning, Benefits & Best Tools

- Research Paper Outline: Free Templates & Examples to Guide You

- How to Write a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Lab Report: Examples from Academic Editors

- Research Methodology Guide: Writing Tips, Types, & Examples

- The 10 Best Essential Resources for Academic Research

- 100+ Useful ChatGPT Prompts for Thesis Writing in 2024

- Best ChatGPT Prompts for Academic Writing (100+ Prompts!)

- Sampling Methods Guide: Types, Strategies, and Examples

- Independent vs. Dependent Variables | Meaning & Examples

- Top 10 AI Tools for Research in 2024 (Fast & Efficient!)

- Understanding Verbatim Plagiarism: Copy, Paste, Regret

- What Is a Journal Article and How to Write a Journal Article

- How to Use AI to Write Research Papers: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Difference Between Paper Editing and Peer Review

- How to Handle Journal Rejection: Essential Tips

- Editing and Proofreading Academic Papers: A Short Guide

- How to Carry Out Secondary Research

- The Results Section of a Dissertation

- Final Checklist: Is My Article Ready for Submitting to Journals?

- Types of Research Articles to Boost Your Research Profile

- 8 Types of Peer Review Processes You Should Know

- How does LaTeX based proofreading work?

- How to Improve Your Scientific Writing: A Short Guide

- Chicago Title, Cover Page & Body | Paper Format Guidelines

- How to Write a Thesis Statement: Examples & Tips

- Chicago Style Citation: Quick Guide & Examples

- Research Paper Outline: Free Templates & Examples to Guide You

- The A-Z Of Publishing Your Article in A Journal

- What is Journal Article Editing? 3 Reasons You Need It

- 5 Effective Personal Statement Examples & Templates

- Complete Guide to MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Book in APA Style | Format & Examples

- How to Start a Research Paper | Step-by-step Guide

- APA Citations Made Easy with Our Concise Guide for 2024

- A Step-by-Step Guide to APA Formatting Style (7th Edition)

- Top 10 Online Dissertation Editing Services of 2024

- Academic Writing in 2024: 5 Key Dos & Don’ts + Examples

- How to Write a Lab Report: Examples from Academic Editors

- What Are the Standard Book Sizes for Publishing Your Book?

- MLA Works Cited Page: Quick Tips & Examples

- 2024’s Top 10 Thesis Statement Generators (Free Included!)

- Top 10 Title Page Generators for Students in 2024

- What Is an Open Access Journal? 10 Myths Busted!

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources: Definition, Types & Examples

- How To Write a College Admissions Essay That Stands Out

- How to Write a Dissertation & Thesis Conclusion (+ Examples)

- APA Journal Citation: 7 Types, In-Text Rules, & Examples

- What Is Predatory Publishing and How to Avoid It!

- Independent vs. Dependent Variables | Meaning & Examples

- What Is Plagiarism? Meaning, Types & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Dissertation & Thesis Introduction

- How to Cite a Book in MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Website in MLA Format | 9th Edition Rules

- 10 Best AI Conclusion Generators (Features & Pricing)

- Top 10 Academic Editing Services of 2024 [with Pricing]

- 100+ Writing Prompts for College Students (10+ Categories!)

- How to Create the Perfect Thesis Title Page in 2024

- What Is Accidental Plagiarism & 9 Prevention Strategies

- What Is Self-Plagiarism? (+ 7 Prevention Strategies!)

- Understanding Verbatim Plagiarism: Copy, Paste, Regret

- Improve Academic Writing: Types, Tips, Examples, Services

- What Is a Journal Article and How to Write a Journal Article

- What Is Paraphrasing Plagiarism and How to Avoid It

- 50 Best Essay Prompts for College Students in 2024

- What Is Expository Writing? Types, Examples, & 10 Tips

- Academic Research Ethics & Rules Simplified for All

- Preventing Plagiarism in Your Thesis: Tips & Best Practices

- Final Submission Checklist | Dissertation & Thesis

- 7 Useful MS Word Formatting Tips for Dissertation Writing

- How to Write a MEAL Paragraph: Writing Plan Explained in Detail

- How does LaTeX based proofreading work?

- Em Dash vs. En Dash vs. Hyphen: When to Use Which

- 2024’s Top 10 Self-Help Books for Better Living

- Top 10 Paper Editing Services of 2024 (Costs & Features)

- Top 10 AI Proofreaders to Perfect Your Writing in 2024

- 100+ Useful ChatGPT Prompts for Thesis Writing in 2024

- Best ChatGPT Prompts for Academic Writing (100+ Prompts!)

- MLA Works Cited Page: Quick Tips & Examples

- 2024’s Top 10 Thesis Statement Generators (Free Included!)

- Top 10 Title Page Generators for Students in 2024

- What Is Plagiarism? Meaning, Types & Examples

- 10 Advanced AI Text Editors to Transform Writing in 2024

- Top 10 Academic Editing Services of 2024 [with Pricing]

- The 10 Best Free Character and Word Counters of 2024

- Know Everything About How to Make an Audiobook

- How to Create the Perfect Thesis Title Page in 2024

- Top 10 Academic Proofreading Services & How They Help

- Mastering Metaphors: Definition, Types, and Examples

- 10 Best Paid & Free Citation Generators (Features & Costs)

- Citing References: APA, MLA, and Chicago

- How to Cite Sources in the MLA Format

- MLA Citation Examples: Cite Essays, Websites, Movies & More

- Chicago Title, Cover Page & Body | Paper Format Guidelines

- Chicago Style Citation: Quick Guide & Examples

- Complete Guide to MLA Format (9th Edition)

- Citations and References: What Are They and Why They Matter

- APA Headings & Subheadings | Formatting Guidelines & Examples

- Formatting an APA Reference Page | Template & Examples

- Research Paper Format: APA, MLA, & Chicago Style

- How to Create an MLA Title Page | Format, Steps, & Examples

- How to Create an MLA Header | Format Guidelines & Examples

- MLA Annotated Bibliography | Guidelines and Examples

- APA Website Citation (7th Edition) Guide | Format & Examples

- APA Citations Made Easy with Our Concise Guide for 2024

- APA Citation Examples: The Bible, TED Talk, PPT & More

- APA Header Format: 5 Steps & Running Head Examples

- APA Title Page Format Simplified | Examples + Free Template

- A Step-by-Step Guide to APA Formatting Style (7th Edition)

- How to Write an Abstract in MLA Format: Tips & Examples

- APA Journal Citation: 7 Types, In-Text Rules, & Examples

- 10 Best Free Plagiarism Checkers | Accurate & Reliable Tools

- 5 Reasons to Cite Your Sources Properly | Avoid Plagiarism!

- How to Cite a Book in MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Website in MLA Format | 9th Edition Rules

- 10 Best Paid & Free Citation Generators (Features & Costs)

- Writing a Dissertation Proposal

- The Acknowledgments Section of a Dissertation

- The Table of Contents Page of a Dissertation

- The Introduction Chapter of a Dissertation

- The Literature Review of a Dissertation

- Tips to Self-Edit Your Dissertation

- The Results Section of a Dissertation

- Preventing Plagiarism in Your Thesis: Tips & Best Practices

- Final Submission Checklist | Dissertation & Thesis

- The Only Dissertation Toolkit You’ll Ever Need!

- 7 Useful MS Word Formatting Tips for Dissertation Writing

- 5 Thesis Writing Tips for Master Procrastinators

- A Beginner’s Guide to How to Write a Dissertation in 2024

- The 5 Things to Look for in a Dissertation Editing Service

- Top 10 Dissertation Editing & Proofreading Services

- Why is it important to add references to your thesis?

- Thesis Editing | Definition, Scope & Standard Rates

- Top 10 Online Dissertation Editing Services of 2024

- Expert Formatting Tips on MS Word for Dissertations

- A 7-Step Guide on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

- 350 Best Dissertation Topic Ideas for All Streams in 2024

- A Guide on How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- Dissertation Defense: What to Expect and How to Prepare

- Creating a Dissertation Title Page (Examples & Templates)

- Essential Research Tips for Essay Writing

- How to Write a MEAL Paragraph: Writing Plan Explained in Detail

- How to Write a Thesis Statement: Examples & Tips

- What Is a Mind Map? Free Mind Map Templates & Examples

- How to Write an Essay Outline: Free Template & Examples

- How to Write an Essay Header: MLA and APA Essay Headers

- What Is an Essay? A Comprehensive Guide to Structure and Types

- How to Write an Essay: 8 Simple Steps with Examples

- The Four Main Types of Essay | Quick Summary with Examples

- Expository Essay: Structure, Tips, and Examples

- Guide to Essay Editing: Methods, Tips, & Examples

- Narrative Essays: Structure, Tips, and Examples

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay (Examples Included)

- How to Write a Descriptive Essay | Examples and Structure

- How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Examples & Steps

- How to Write a Conclusion for an Essay (Examples Included!)

- How to Write an Impactful Personal Statement (Examples Included)

- Literary Analysis Essay: 5 Steps to a Perfect Assignment

- How to Write a Compare and Contrast Essay: Tips & Examples

- Top 10 Essay Checkers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- 100 Best College Essay Topics & How to Pick the Perfect One!

- College Essay Format: Tips, Examples, and Free Template

- Structure of an Essay: 5 Tips to Write an Outstanding Essay

- 10 Best AI Essay Outline Generators of 2024

- The Best Essay Graders of 2024 That You Can Use for Free!

- Top 10 Free Essay Writing Tools for Students in 2024

- Personal Statement Editing Services: Craft a Winning Essay

- College Essay Review: A Step-by-Step Guide (With Examples)

- Top 10 Best AI Essay Writing Tools in 2024

- Top 10 Essay Editing Services of 2024

- Top 10 College Essay Review Services: Pricing and Benefits

- How to Write an Assignment: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students

Still have questions? Leave a comment

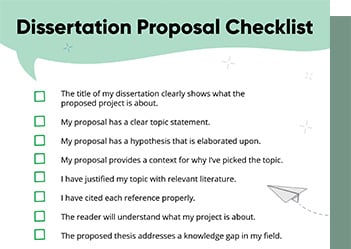

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Examples: Edited Papers

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Need

Editing and

Proofreading Services?

How to Improve Your Scientific Writing: A Short Guide

Dec 12, 2022

Dec 12, 2022 5

min read

5

min read

- Tags: Academic Writing, Editing

The key characteristic of scientific writing is clarity. Just as a signal of any kind is useless unless it is received, a published scientific paper (signal) is useless unless it is received as well as understood by its intended audience. So, scientific writing is a creative process.

Scientific writing is designed to convey scientific information clearly and concisely to other scientists and students through case reports, technical notes, journal articles or scientific reviews, and it’s one tough process to master.

Scientific writing often is a difficult and arduous task for new students. And rightly so, as it entails following various rules, different format and deviates in terms of structure from how we are initially taught to write for other subjects.

Freshers commit many mistakes in these papers, because they focus almost exclusively on the scientific process, disregarding the writing process. Here is a succinct guide that lays out strategies for effective scientific writing to help you increase the focus on conveying your findings more effectively while writing in the college classroom and which will help you later for publishing scientific journals.

Take the Scientific Storytelling Approach

Robert Boyle, a pioneer of the modern scientific experimental method, emphasized the importance of not boring the reader with a dull, flat style.

Science is about facts and objectivity, not hyperbole to sell a story. However, objectivity is not at odds with adding a creative element to your writing or making it clearer and more interesting to read.

Everyone has great stories about their research. Discreetly slip these into your work. Humans are programmed to love a story and will remember facts embedded in stories longer than factoids alone.

Tense & Style

Some style guides discourage the use of the passive voice, others encourage it. While some journals prefer using “we” rather than “I” as the personal pronoun. Note that “we” sometimes includes the reader.

Be careful to keep the verb tense consistent within sections of your paper. The Results section of a paper is usually in the past tense because the experiments have already been done.

General principles disclosed by experimentation can be described in the present tense, since the conclusion is based on eternal facts.

One idea per paragraph

Make it easy for readers by presenting a single idea in each paragraph. While editing, try to improve your prose by breaking a lengthy complicated 9-sentence paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs with a single idea presented in each. Varying sentence lengths are recommended for all kinds of writing; it applies to scientific writing as well.

Citations: Explain Strong Claims in Detail

A big problem with much of science writing and in many student essays is that the writing presents strong claims with nothing more than a citation to support it.

Let’s take a look at an example:

“When newbie scientists deal with too much data during an experiment, information overload can lead them to draw erroneous conclusions (Jones & Nash, 2012).”

Now, that’s a strong claim. It’s a big deal, if true. But readers often start wondering, “How exactly do they know this?” “What’s their data?” “What study did they run?”

It would be better to expound this claim by explaining how Jones and Nash know this. The writing could say:

“Jones and Nash supervised 500 budding scientists in the Pennsylvania University Chemistry Lab and found that the least experienced scientists involved in complex experiments were more likely to draw erroneous conclusions.”

Which one do you think gives more insight into the study?

Most scientific writing follows one of three citation styles:

• AMA (American Medical Association)

• APA (American Psychological Association)

• CSE (Council of Science Editors)

Editing and Proofreading

Once you’ve finished writing, come back to your paper and validate your presentation of facts and claims. Are there any gaps in your paper’s structure? Have things been explained clearly? Does a point seem hard to understand because of awkward writing?

Re-read the paper with a finer lens, well-structured sentences and appropriate word choice make a huge difference. Grammar and spelling are just as important as your scientific story; a poorly written paper makes a limited impact irrespective of the presented ideas.

It’s a fact that 90% of the scientific journals are published only in English. PaperTrue has a dedicated team of editors who specialize in editing papers on scientific topics. We’ve refined tons of papers to the absolute satisfaction of our clients. Now, students and scientists can solely focus on just the research and writing, and leave finishing the paper to PaperTrue. With our high-grade editing and proofreading, we ensure you get published in the top journals.

Books and Resources

These are some tools available online that will aid you in writing diligently:

CAS abbreviation and acronyms

A dictionary of Units of Measurement

SWAN

The following books are available in PDF; you can download and save them for a deeper understanding of the scientific writing process:

Christine B. Feak/ John M. Swales: Telling a Research Story. Writing a Literature Review. The University of Michigan Press 2009.

Robert A. Day/ Barbara Gastel: How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper.

Keep in mind that there is no single correct way to write a scientific paper. Even professional scientists feel that they can always write more effectively. Keep experimenting and seek support if you like, and as you gain experience, you will begin to find your own voice. Good luck and happy writing!