- Tips to Self-Edit Your Dissertation

- Guide to Essay Editing: Methods, Tips, & Examples

- Journal Article Proofreading: Process, Cost, & Checklist

- The A–Z of Dissertation Editing: Standard Rates & Involved Steps

- Research Paper Editing | Guide to a Perfect Research Paper

- Dissertation Proofreading | Definition & Standard Rates

- Thesis Proofreading | Definition, Importance & Standard Pricing

- Research Paper Proofreading | Definition, Significance & Standard Rates

- Essay Proofreading | Options, Cost & Checklist

- Top 10 Paper Editing Services of 2024 (Costs & Features)

- Top 10 Essay Checkers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- Top 10 AI Proofreaders to Perfect Your Writing in 2024

- Top 10 English Correctors to Perfect Your Text in 2024

- 10 Advanced AI Text Editors to Transform Writing in 2024

- Personal Statement Editing Services: Craft a Winning Essay

- Top 10 Academic Proofreading Services & How They Help

- College Essay Review: A Step-by-Step Guide (With Examples)

- Top 10 College Essay Review Services: Pricing and Benefits

- How to Edit a College Admission Essay (8-Step Guide)

- Improve Academic Writing: Types, Tips, Examples, Services

- How to Use AI to Write Research Papers: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write an Assignment: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students

- AI Proofreading Services: Meaning, Benefits & Best Tools

- 10 Best Proofreading Services Online for All in 2025

- Research Paper Outline: Free Templates & Examples to Guide You

- How to Write a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Lab Report: Examples from Academic Editors

- Research Methodology Guide: Writing Tips, Types, & Examples

- The 10 Best Essential Resources for Academic Research

- 100+ Useful ChatGPT Prompts for Thesis Writing in 2024

- Best ChatGPT Prompts for Academic Writing (100+ Prompts!)

- Sampling Methods Guide: Types, Strategies, and Examples

- Independent vs. Dependent Variables | Meaning & Examples

- Top 10 AI Tools for Research in 2024 (Fast & Efficient!)

- Understanding Verbatim Plagiarism: Copy, Paste, Regret

- What Is a Journal Article and How to Write a Journal Article

- How to Use AI to Write Research Papers: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Difference Between Paper Editing and Peer Review

- How to Handle Journal Rejection: Essential Tips

- Editing and Proofreading Academic Papers: A Short Guide

- How to Carry Out Secondary Research

- The Results Section of a Dissertation

- Final Checklist: Is My Article Ready for Submitting to Journals?

- Types of Research Articles to Boost Your Research Profile

- 8 Types of Peer Review Processes You Should Know

- How does LaTeX based proofreading work?

- How to Improve Your Scientific Writing: A Short Guide

- Chicago Title, Cover Page & Body | Paper Format Guidelines

- How to Write a Thesis Statement: Examples & Tips

- Chicago Style Citation: Quick Guide & Examples

- Research Paper Outline: Free Templates & Examples to Guide You

- The A-Z Of Publishing Your Article in A Journal

- What is Journal Article Editing? 3 Reasons You Need It

- 5 Effective Personal Statement Examples & Templates

- How to Cite a Book in APA Style | Format & Examples

- How to Start a Research Paper | Step-by-step Guide

- APA Citations Made Easy with Our Concise Guide for 2024

- A Step-by-Step Guide to APA Formatting Style (7th Edition)

- Academic Writing in 2024: 5 Key Dos & Don’ts + Examples

- How to Write a Lab Report: Examples from Academic Editors

- What Are the Standard Book Sizes for Publishing Your Book?

- MLA Works Cited Page: Quick Tips & Examples

- 2024’s Top 10 Thesis Statement Generators (Free Included!)

- Top 10 Title Page Generators for Students in 2024

- What Is an Open Access Journal? 10 Myths Busted!

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources: Definition, Types & Examples

- How To Write a College Admissions Essay That Stands Out

- APA Journal Citation: 7 Types, In-Text Rules, & Examples

- What Is Predatory Publishing and How to Avoid It!

- Independent vs. Dependent Variables | Meaning & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Dissertation & Thesis Introduction

- How to Cite a Book in MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Website in MLA Format | 9th Edition Rules

- 10 Best AI Conclusion Generators (Features & Pricing)

- Top 10 Academic Editing Services of 2024 [with Pricing]

- 100+ Writing Prompts for College Students (10+ Categories!)

- How to Create the Perfect Thesis Title Page in 2024

- What Is Accidental Plagiarism & 9 Prevention Strategies

- What Is Self-Plagiarism? (+ 7 Prevention Strategies!)

- Understanding Verbatim Plagiarism: Copy, Paste, Regret

- Improve Academic Writing: Types, Tips, Examples, Services

- What Is a Journal Article and How to Write a Journal Article

- What Is Paraphrasing Plagiarism and How to Avoid It

- 50 Best Essay Prompts for College Students in 2024

- What Is Expository Writing? Types, Examples, & 10 Tips

- Academic Research Ethics & Rules Simplified for All

- Complete Guide to MLA 9th Format

- Top 10 Online Dissertation Editing Services of 2025

- What Is Plagiarism? Meaning, Types & Examples

- How to Write a Dissertation & Thesis Conclusion (+ Examples)

- Preventing Plagiarism in Your Thesis: Tips & Best Practices

- Final Submission Checklist | Dissertation & Thesis

- 7 Useful MS Word Formatting Tips for Dissertation Writing

- How to Write a MEAL Paragraph: Writing Plan Explained in Detail

- How does LaTeX based proofreading work?

- Em Dash vs. En Dash vs. Hyphen: When to Use Which

- 2024’s Top 10 Self-Help Books for Better Living

- Top 10 Paper Editing Services of 2024 (Costs & Features)

- Top 10 AI Proofreaders to Perfect Your Writing in 2024

- 100+ Useful ChatGPT Prompts for Thesis Writing in 2024

- Best ChatGPT Prompts for Academic Writing (100+ Prompts!)

- MLA Works Cited Page: Quick Tips & Examples

- 2024’s Top 10 Thesis Statement Generators (Free Included!)

- Top 10 Title Page Generators for Students in 2024

- 10 Advanced AI Text Editors to Transform Writing in 2024

- Top 10 Academic Editing Services of 2024 [with Pricing]

- The 10 Best Free Character and Word Counters of 2024

- Know Everything About How to Make an Audiobook

- How to Create the Perfect Thesis Title Page in 2024

- Top 10 Academic Proofreading Services & How They Help

- Mastering Metaphors: Definition, Types, and Examples

- 10 Best Paid & Free Citation Generators (Features & Costs)

- What Is Plagiarism? Meaning, Types & Examples

- Citing References: APA, MLA, and Chicago

- How to Cite Sources in the MLA Format

- MLA Citation Examples: Cite Essays, Websites, Movies & More

- Chicago Title, Cover Page & Body | Paper Format Guidelines

- Chicago Style Citation: Quick Guide & Examples

- Citations and References: What Are They and Why They Matter

- APA Headings & Subheadings | Formatting Guidelines & Examples

- Formatting an APA Reference Page | Template & Examples

- Research Paper Format: APA, MLA, & Chicago Style

- How to Create an MLA Title Page | Format, Steps, & Examples

- How to Create an MLA Header | Format Guidelines & Examples

- MLA Annotated Bibliography | Guidelines and Examples

- APA Website Citation (7th Edition) Guide | Format & Examples

- APA Citations Made Easy with Our Concise Guide for 2024

- APA Citation Examples: The Bible, TED Talk, PPT & More

- APA Header Format: 5 Steps & Running Head Examples

- APA Title Page Format Simplified | Examples + Free Template

- A Step-by-Step Guide to APA Formatting Style (7th Edition)

- How to Write an Abstract in MLA Format: Tips & Examples

- APA Journal Citation: 7 Types, In-Text Rules, & Examples

- 10 Best Free Plagiarism Checkers | Accurate & Reliable Tools

- 5 Reasons to Cite Your Sources Properly | Avoid Plagiarism!

- How to Cite a Book in MLA Format (9th Edition)

- How to Cite a Website in MLA Format | 9th Edition Rules

- 10 Best Paid & Free Citation Generators (Features & Costs)

- Complete Guide to MLA 9th Format

- Writing a Dissertation Proposal

- The Acknowledgments Section of a Dissertation

- The Table of Contents Page of a Dissertation

- The Introduction Chapter of a Dissertation

- The Literature Review of a Dissertation

- Tips to Self-Edit Your Dissertation

- The Results Section of a Dissertation

- Preventing Plagiarism in Your Thesis: Tips & Best Practices

- Final Submission Checklist | Dissertation & Thesis

- The Only Dissertation Toolkit You’ll Ever Need!

- 7 Useful MS Word Formatting Tips for Dissertation Writing

- 5 Thesis Writing Tips for Master Procrastinators

- A Beginner’s Guide to How to Write a Dissertation in 2024

- The 5 Things to Look for in a Dissertation Editing Service

- Top 10 Dissertation Editing & Proofreading Services

- Why is it important to add references to your thesis?

- Thesis Editing | Definition, Scope & Standard Rates

- Expert Formatting Tips on MS Word for Dissertations

- A 7-Step Guide on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

- 350 Best Dissertation Topic Ideas for All Streams in 2024

- A Guide on How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- Dissertation Defense: What to Expect and How to Prepare

- Creating a Dissertation Title Page (Examples & Templates)

- Top 10 Online Dissertation Editing Services of 2025

- Essential Research Tips for Essay Writing

- How to Write a MEAL Paragraph: Writing Plan Explained in Detail

- How to Write a Thesis Statement: Examples & Tips

- What Is a Mind Map? Free Mind Map Templates & Examples

- How to Write an Essay Outline: Free Template & Examples

- How to Write an Essay Header: MLA and APA Essay Headers

- What Is an Essay? A Comprehensive Guide to Structure and Types

- How to Write an Essay: 8 Simple Steps with Examples

- Expository Essay: Structure, Tips, and Examples

- Guide to Essay Editing: Methods, Tips, & Examples

- Narrative Essays: Structure, Tips, and Examples

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay (Examples Included)

- How to Write a Descriptive Essay | Examples and Structure

- How to Write a Conclusion for an Essay (Examples Included!)

- How to Write an Impactful Personal Statement (Examples Included)

- Literary Analysis Essay: 5 Steps to a Perfect Assignment

- How to Write a Compare and Contrast Essay: Tips & Examples

- Top 10 Essay Checkers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- 100 Best College Essay Topics & How to Pick the Perfect One!

- College Essay Format: Tips, Examples, and Free Template

- Structure of an Essay: 5 Tips to Write an Outstanding Essay

- 10 Best AI Essay Outline Generators of 2024

- The Best Essay Graders of 2024 That You Can Use for Free!

- Top 10 Free Essay Writing Tools for Students in 2024

- Personal Statement Editing Services: Craft a Winning Essay

- College Essay Review: A Step-by-Step Guide (With Examples)

- Top 10 Best AI Essay Writing Tools in 2024

- Top 10 Essay Editing Services of 2024

- Top 10 College Essay Review Services: Pricing and Benefits

- How to Write an Assignment: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students

- The Four Main Types of Essay | Quick Summary with Examples

- How to Write an Essay Introduction | 4 Examples & Steps

Still have questions? Leave a comment

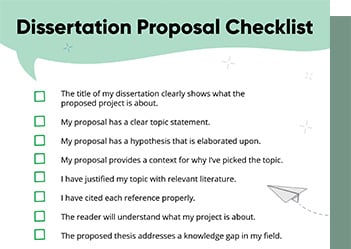

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Examples: Edited Papers

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Need

Editing and

Proofreading Services?

8 Types of Peer Review Processes You Should Know

Aug 05, 2022

Aug 05, 2022 5

min read

5

min read

If you’re a student or researcher looking to get published in reputed academic journals, expect your paper to go through an extensive peer review process. What is peer review and why is it important? You might have heard your professors/advisors mention the phrase when they are talking about scholarly work. Let’s dive straight into it!

Every discipline has journals dedicated to publishing new research done within that field. From natural sciences to mathematics, there are journals for every subject possible. There are journals for even specific subdisciplines of a subject. For example, within biology journals, you will find a host of journals about biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology.

With over 30,000 journals across the world and over 2 million articles being published each year, there is a lot of academic research that is generated each year! But how does the academic community know which ones of those are legitimate? If it is becoming increasingly easier to get published, how do they know which work is groundbreaking?

Which ones of those are well researched and scientifically valid? That’s what the peer review process determines.

What is peer review?

Peer review is a process in which a researcher’s work is critically evaluated by experts from the researcher’s field before it is published in a journal or a conference proceeding. This means that articles published in peer-reviewed journals are those vetted and verified as relevant research for the advancement of the subject.

Peer reviewers help journal editors decide whether an article is fit for publication, needs minor or major revision, or whether it should be rejected altogether.

Why is peer review important?

The peer-review process has been considered as a hallmark of producing good scientific research for over 300 years. It rules out false claims, lack of evidence, inconsistency in arguments and other kinds of biases. The general consensus is that experts of a field are the most qualified to determine how the field advances, and to help improve the quality of research in a subject.

While the final decision of publication is on the editor, peers play an important role in assessing the scientific validity of academic research.

The peer-review process

While the variables of the peer review process are different from journal to journal, it usually follows these steps:

- A researcher submits their paper to a prospective journal.

- The journal’s editorial team evaluates it to see if the research is relevant to the publication.

- Depending on how the editor’s review goes, the journal may

- Accept the paper, which then goes for expert review.

- Reject the paper, with an option to resubmit after the researcher has made revisions.

- Reject the paper entirely.

- If your paper has been accepted, it will go through a round of peer review, usually comprising one to three experts in your field.

- Depending on how the research has been critiqued, you may have to revise your paper.

- Once revisions have been accepted, your paper is ready for publication.

There are many variations of this process, and what applies to your paper depends on the subject and journal guidelines.

These peers, also known as referees, then review your work.

What do they look for?

- Valid, reliable, and replicable research methods

- A well-argued, comprehensive paper

- Impact and contribution to the field of study

Now that we’ve answered some of the most important questions about the peer review process, let’s explore the different types of peer review processes.

8 types of peer review processes

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of peer review processes: closed and open. In a closed peer review process, the identities of some or all parties involved are anonymous. On the other hand, open peer review processes encourage that the identities of reviewers and authors be known, in an effort to encourage transparency and accountability. Within these two broader types, there are many systems of peer review used across journals and disciplines. Let’s take a look!

1. Single blind review

In a single blind review (or single anonymized review), the author’s identity is known to the reviewers, while the reviewers’ identity is anonymous to the author. This is the most commonly practiced form of peer review.

This kind of anonymity ensures that the reviewers can critique the work without the pressure of authors being able to respond to them personally. Ideally, this and having details about authors will give them more context to work with.

The flip side of this format is that knowing the author’s identity, affiliation, and research history may also result in a biased critique. Peers may be prone to bias based on an author’s gender identity, academic background, nationality, and so on.

2. Double blind review

In a double blind review (or double anonymized review), the identities of both the reviewers and authors are unknown to each other. This form of peer review is common in social science and humanities journals.

Double blind reviews ensure impartial review. It allows reviewers to judge papers based on the merit of the research and the ideas it poses, rather than the author and their affiliations. But despite the anonymity, researchers and reviewers often may be able to identify each other, since they are likely to be from the same research work. Reviewers may also be able to identify authors based on writing style, the sources they cite, self citations, and even the topic of research.

3. Triple blind review

In the triple anonymized review system, the author’s identity is anonymous to both the reviewer and the journal editors (until the first round of reviews). Likewise, their identity is unknown to the author as well. This form of review is quite rare currently and is a fairly recent conversation within academia.

While the triple blind review system is poised to reduce bias among all involved parties, it’s still possible for reviewers and editors to identity the author (just like in a double blind review. The bigger constraint is that the logistics of ensuring this level of anonymity is complex, often adding administrative hurdles and increasing publishing costs.

4. Open peer review

Open peer review is an umbrella term that encompasses review systems where the identities of the authors and their reviewers are known to each other. This can either be during the review process or after the paper has been published.

In some cases, peer-reviewed journals may choose to publish the review alongside your article. Making the review publically available encourages accountability and transparency among peers. Having open conversations about current research improves discourse and the overall quality of research produced in the subject.

Despite its many advantages, open reviews are still fairly unpopular since many researchers are apprehensive about being identified for their review style.

5. Transparent peer review

This is a form of peer review in which the researcher’s identity is known to the reviewers, while the latter’s identity is anonymous. So far it sounds like the single blind review, but what makes this transparent is that authors have a chance to know who their reviewers are, provided they agree to disclose their identity. They also have to sign a report stating so.

If the article has been accepted for publication, the review is published anonymously with the article.v

6. Transferable peer review

There are instances, in scientific circles, where a journal might reject a paper if they think the research is not relevant to their publication. For researchers, this is a step backwards because they have to start all over again to find journals appropriate for their work, as well as format and revise their papers accordingly.

The research community is increasingly exploring a form of peer review to make this process easier: the transferable peer review system. Under this system, a journal that deems your work unsuitable for publication may recommend you to a journal that’s more relevant to your field and much more likely to align with your research area.

While this is a wonderful way to support researchers, this system presents a lot of logistical hurdles for the journal. Plus, there’s no guarantee that the second journal will publish your paper. That’s still on the merit of your research!

7. Collaborative peer review

The collaborative peer review model is also a fairly new system. As the name suggests, under this model, the author gets to discuss their research with their reviewer(s). The reviewers’ identities are usually anonymous, with both parties communicating via email or through a communication platform set up by the journal.

This model ensures real-time feedback and exchange of notes between parties. There’s more scope for the researcher to receive in-depth feedback and make necessary revisions swiftly. The flip side of this model, however, is that it’s often logistically difficult for journals to invest the time, effort, and resources to hone the work of every researcher that comes their way.

8. Post-publication peer review

On one level, all published research is liable to be under the scrutiny of the research community, It’s fair game, after all, and (more importantly) expected that it continuously lives up to the quality of research produced in that field.

But since academia is competitive and there’s constant pressure to publish work, the research community is also exploring a form of peer review that keeps up with rapid publication of papers. This is known as post-publication peer review (PPPR), where peers can respond to a paper after it has been published. Reviews can be sent in by email, letters to the journal, blogs, social media, and discussion forums.